Why I don't think "The Substance" Lived Up to the Hype

The film just won three Critics Choice Awards. But it didn't click with me. At all.

“It’s me! It’s Liz! It’s Sue!“ The mutated blob of flesh, wrapped in a blue sequin night-gown for the New Year’s Eve celebration, grasps onto the microphone and pleads to the crowd. A tit hangs here. A face pokes out there. It wears Lou’s beautiful photograph like as a helpless and useless disguise of its true grotesque.

I sat in the dark theater with my silent anger, watching the creature extending her arms as if to hold someone, yet only to be pushed around over and over again. “Monster!” The audience, who is now drenched in her blood, cries out loud. The ending was my least favorite part of the movie. I wanted to scoff. I wanted to cry. I wanted to ask: why — why would you stand on that stage and pledge to the people who have betrayed and deserted you?

Why, toward the very end, are you still seeking their approval?

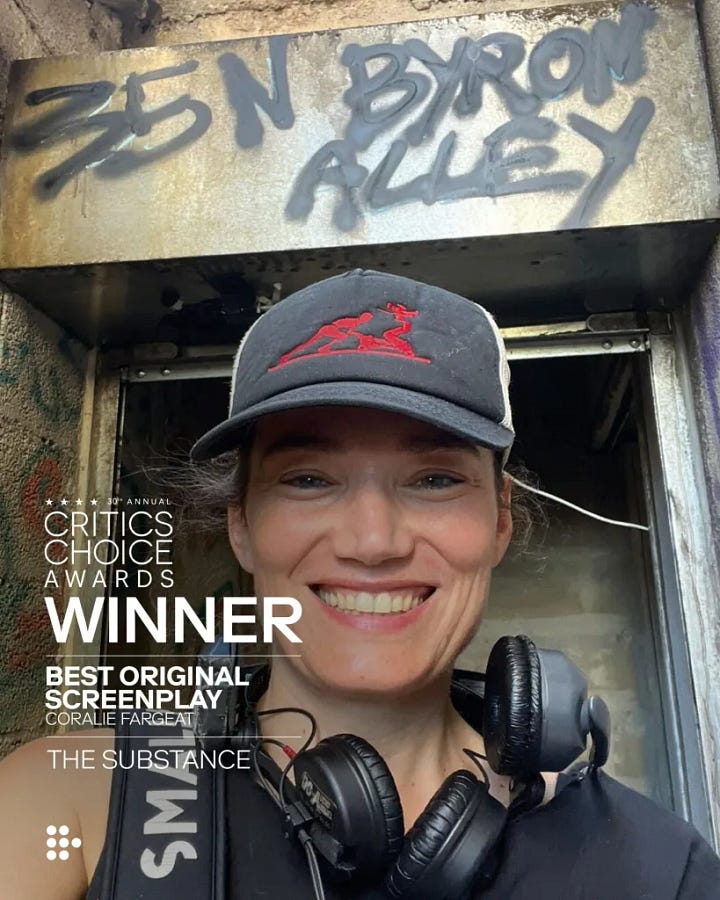

The Substance has just won three critics awards: Best Actress, Best Hair & Makeup, and Best Original Screenplay.

I have absolutely no complaint on the first two. Demi Moore’s powerful performance was grappling. Her portrayal of an aging women deserted not only by a vanity-filled world but ultimately her own self was soul wrenching. As for hair and makeup, the over-aged Elizabeth’s face was a nightmare I could not forget after the movie, only making Lou’s brilliance and vibrance more ironic.

However, I’m surprised to find the script receiving so much buzz and praise when the story, the concept, and the character development in “The Substance” ultimately feel extremely personal and somewhat compromised.

Since it’s debut, The Substance has been placed on a pedestal. Critics flocked after the film for its vivid exposure of the male gaze, the complex self-loathing of ageing women, and the idea that a woman’s value is directly proportional to her age, aka, sexiness.

The Substance is a satirical body-horror and science fiction film underpinned by feminist critique. The film examines the obsession with female beauty and youth, the invisibility of ageing women, and the voracious consumption of women’s bodies in Hollywood’s star system.

If this film came out 20, or 10 years back where feminist awareness around objectification and the intersectionality between sexism and ageism had barely awakened, it would justify all the glory critics have been showering it with. However, in year 2025, the film felt plain and predictable.

At the beginning of the film, the audience is introduced to Elisabeth Sparkle, a fitness superstar once loved by the public during her youth. But as she became older, she was washed out of the television world like an expired box of salad. Her posters that once filled the entire hallway were gone overnight. The TV fitness sensation finally lost its sparks.

In despair, Elisabeth turned to a new substance claiming it would allow her to split her cells and produce a younger, thus better version of self. The substance has some simple rules:

You only split once.

You switch every 7 days, no exception.

As a result, the audience already knows what will go wrong later in the film: one of them will break the 7-day swapping routine, and one of them will end up trying to duplicate themselves again.

Throughout the film, I get this feeling that Coral Fargeat never meant for the audience to like either of the female protagonists.

Elisabeth is often cynical, angry, and full of self-loathing. Ultimately, she detests her ageing self more than any men in the industry who ridiculed her behind her back. At one moment, Elisabeth tries to embrace her aged self by reconnecting with an old classmate who’s always had a crush on her. But the lovely little date ends heartbreakingly with Elisabeth repeatedly comparing herself to Sue, changing her outfit and makeup until she looks like a clown in the mirror, and eventually ghosting the only man throughout the story who wholeheartedly believes her to be beautiful regardless of her age.

Sue, on the other hand, is a typical arrogant, beautiful young girl who has no problem taking from others and obviously believes the world should revolve around her. Fully enjoying her youth and popularity, Sue looks down on Elisabeth and eventually comes to conclusion that her older self is worthless except for serving as the reservoir to keep her youth going. And when she realizes Elisabeth has intended to kill her, she takes revenge and bashes her head in without an ounce of remorse. The only time the audience sees a devastated, desperate Sue is when her body begins to fall apart, and then, when she realizes a corpse cannot produce the fluid she needs to maintain her youth and livelihood.

The relationship between Elisabeth and Sue resembles a toxic mother-daughter relationship where a rebellious, immature teenage daughter who looks down on her old woman and believes the mother exists to serve her, whereas the silent, enduring mother holds a secret grudge against her youthful, beautiful daughter as if she’d stole her life away.

The two never began on friendly grounds. The irresponsible Sue left the house trashed and switched with Elisabeth, leaving the latter to clean up the mess. Then, in revenge, Elisabeth did the same thing right back, as if to show her who’s the boss. In TV interviews, Sue mocks Elisabeth as what her mother would watch as she was growing up, calling her outdated. In return, Elisabeth stuffs herself with some grotesque, sickening homemade food.

Until both are pushed to the edge, screaming: “You’ve got to control yourself!”

If this absurd down spiral was supposed to be satirical, I guess it’s just not for me.

Positioning Sue as the spoiled, head-over-heels self-indulging young beauty is problematic to begin with. When Sue woke up after being created, it is very obvious she knows what’s going on. She’s in shock and disbelief, and soon amazed by her own sexiness: all those emotions prove to the audience that Sue has Elizabeth’s memory up to the point of splitting. Putting ourselves into her shoes, if our souls entered a better version of ourselves, would we show no compassion toward our older self?

As for Elisabeth, while it is understandable how someone who’s spent her life banking on youthfulness would struggle to cope with ageing, it is hard for me to show her any respect when this woman has given up her agency over her own fate, and chooses to surrender herself to the male gaze that she so deeply detest. Ultimately, she only took matters into her own hand twice: once to use the substance, the second time to try to terminate the experience, which led to a sudden realization that Sue is fulfilling their dreams.

Both women were laughable. Again, I suppose that’s the point of a satire. But it’s not for me.

Demi Moore’s controversial body horror role highlights the ageist attitudes prevalent in today's culture. The younger self, Sue, is often favored over the older Elisabeth, demonstrating the societal preference for youth and beauty. This age-based discrimination creates a competitive dynamic between the two, further straining their cooperation with the serum’s rules. However, the movie's story is much more complex than a straightforward battle between two competing personalities. In fact, just as important as the internal psychology of the story is how external perceptions shape our actions.

— Laura Kelly, Screen Rant

The above quote from Screen Rant was more than accurate. Once again, Laura Kelly provides a sharp, sophisticated, and well-layered review about the film’s intentional focus on the harm of misogyny and male gaze, which leads to not only external suppression, but internal objectification and self-hatred as well, which is far more devastating to a woman’s psyche than the former.

But…

My question is: why make the women, again, the laughing stock?

Can we not talk about all the nuances behind the entertainment world’s toxicity and abuse over the female body, without making the women look like another pathetic case study?

The Substance could’ve gone many different ways after Elisabeth splits and address all the key talk points nonetheless. There could be a malicious revenge plot where Elisabeth and Sue join forces. Sue can still exhaust Elisabeth’s body and we can have the very same ending. You could even take the story in a complete direction, and present a Elisabeth who began to embrace her old age and earned Sue’s respect, and Sue who continued to dominate the screen with her “Pump It Ups.”

Obviously, both versions would be completely different movies, and would be a lot less fun since neither character would behave nearly as hysterically. The reason this horror is satiric is because how the women grappled desperately onto youth and male-defined beauty as their last straw. However, as a woman, I’d much rather see the female protagonists stand up for, instead of against, themselves.

That’s not too much to ask, even in a body horror, right?

As we walked out of the theatre, my friend said the movie felt extremely personal — I couldn’t agree more. In The Substance, women remained silent victims and voluntary accomplices in the patriarchal world of star-making. They abused each other and themselves, fought for the male approval like stray dogs fighting over scrap meat. The only liberation is when Elisabeth/Sue’s flesh finally dissolved and her spirit raises in raining sparkles. Yet can we truly call that liberation, when the last bit of her flesh still crawled onto her star plaque — the very symbol of her objectification and the denial of her value as just a human?

However, is The Substance yet another outcry that goes nothing beyond a personal catharsis and leaves women’s own resolution out of the picture?

“You have to be the beautiful princess. The prince is going to save you, and everybody’s going to love you because you’re going to be beautiful and have those dresses and be nice and gentle and smile. And from a very young age, it shaped the role model that you’re supposed to be. But I felt like the monster. I was not at all this. I wish I were the blonde beautiful girl that the prince is going to love. But I wasn’t at all.” Fargeat said during her interview with IndieWire.

And the movie perfectly depicted that conflicted feeling.

But that story gets old.

Heart-wrenching, frustrating, but old.

I’d rather see women assuming their agency.

If we’re gonna use a substance and turn into a monster in the end, let’s fuck some shit up instead of playing by the books.

And even as monsters, love ourselves.